La Festa di San Giovanni

Ever since I have had a terrace, I have been making the Acqua di San Giovanni (Water of St. John) on a traditional magic night that immediately follows the summer solstice.

Legend says that preparations must begin at sunset on 23 June. I collect different varieties of flowers and aromatic herbs, immerse them in water, and place them outside the house for the whole night so that they can absorb the morning dew. I always include the required herbs (sage, rosemary, mint, lemon verbena, lavender) but don’t have the erba di San Giovanni, hypericum, so if I can forage it (it is easy to find in June), I add that too. The following morning, and after the moon’s power has waned and the dew is dried, the Acqua di San Giovanni exudes special qualities : purifying, curative, and protective from disease, misfortune and envy.

On the morning of 24 June, I use the Acqua to wash my face and hands. I wash my dog’s paws and face in it too, and he always takes a little sip of it as well.

Many parts of Italy have their own St. John’s traditions. John the Baptist is the patron saint of Florence and today there is a city- wide holiday with major festivities and fireworks.

In Tuscany, as my friend Nancy Jenkins reminds me, 23 June is the day to pick the green walnuts and make nocino (walnut liqueur) — but the nuts must all be harvested before the dew has dried on the morning of the 24th.

And Rome, celebrated for its lusty participation in all folklore and customs (all of a pagan nature, sometimes then Christianized), has its own way to celebrate saint John.

Growing up in Rome, my children danced around and jumped over the fuoco di San Giovanni (the thrillingly dangerous Fire of St. John). When the flames burned down to scarlet embers, they toasted bruschetta while singing traditional songs that honored the day and the summer.

When I was a little girl in Rome, late on the evening of 23 June, my mother and I would take tram #8 to Piazza San Giovanni.

It was on 23 June that I first heard the word baraonda, and it has stayed with me forever. It means chaotic disorder, and the Festa di San Giovanni, as celebrated in Piazza San Giovanni, opposite Rome’s major basilica dedicated to the saint, was dramatically just that.

All through the night of 23 June, the witches and the spirits were on the prowl. Some said that they were the spirits of Salome and Herod, who had murdered John the Baptist. They roamed about on brooms, and on the night of 23 June, they assembled with other spirits and got up to major mischief.

The most effective way to force them away was with the baraonda. There were horns, there were drums, there were tambourines. There was lanterns so they could be seen. There were pot lids with wooden spoons. And to my five year old self it was absolutely wonderful !

There was screaming and singing and confusion. The noise so perturbed the witches and the spirits that they could not forage the wild herbs they required to make their spells.

As we wandered through the square, holding hands, my mother told me about coming to Piazza San Giovanni for the Festa when she was little. I loved to hear her tales.

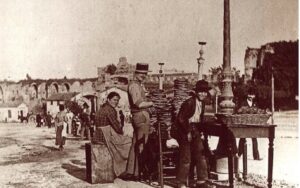

“This is nothing !” she said. “When I was little, there were tables going all the way down Via di San Giovanni in Laterano !” She pointed at the tables that were dotted here and there in the piazza, wooden folding tables identical to the one we kept in the car for picnics. “So few now” (it seemed like many to me), she said wistfully.

Families grouped at these tables, leaning over their plates of…

Snails !

Snails ! For a child, the big fascination of the Festa di San Giovanni, even more fun then seeing adults making the baraonda, was the snails !

In Roman tradition, snails’ horns represented discord and worry. Eating them signified destroying adversity. Romans live their lives in adversity. Romans might have even more adversity if they did not eat snails.

Eating snails ensured peace and prosperity.

When my mother was a little girl, there were not two or three makeshift osterie, as there were now, cooking snails, but the square was full of them ! Snails being cooked, snails being served up, snails being devoured.

“Ah” sighed my mother, “those were other times”, when every centimeter of the square, except where Romans were making baraonda, was filled with snail eaters. She remembered that some of her mother’s friends did not trust the osteria host to purge the snails properly, and would do the job themselves, bringing their own cooked snails to the osteria, where they would settle down with the host’s wine.

“It was more sure for the digestion”, said my mother. Then when I demanded it, she provided me with an unforgettably graphic description of how to purge a snail.

She recalled that at the end of the Festa, the cannon would go off atop Castel Sant’Angelo, thus terminating the jubilee. The baraonda would die down, and, she said (but she never saw it) gold and silver coins were thrown from the basilica balcony into the boisterous crowd below. A shower of gold and silver coins ! I loved this image. But the…

Snails !

The snails were on the plates, and the white porcelain background made the platters of snails seem all the more remarkable. They were morsels heavily covered in a thick sugo of tomato and onion and anchovy and mint and being spooned into the mouths of the Romans. The plates were just at my height as we walked by so I could look at the snails, eye to eye.

They smelled wonderful and comforting, like our kitchen at home, of cucina casalinga. That sauce looked delicious too. But I was five and a bit wise so I knew that under that nice sauce there was something foreign, something I had never eaten. It was…

Snails !

The snail farmers, the lumacari, were doing big business. The lumacari had set up their tables and on them in huge wicker baskets, and in enormous jars, were the snails. Being nocturnal and likely also disturbed by the baraonda, the snails were on the prowl. When the lumacaro opened the lid of his basket or picked the glass sheet off his jar, inevitably several snails would escape. And crawl onto the table and down the table legs. This is what I remember best about the Festa di San Giovanni.

Pulling my mother close to one of the lumacaro’s tables and drawing close to the snails, I watched their quivering, questing horns, all with a combination of fascination, a little revulsion and also compassion. Because if the lumacaro should lean down and snatch back his snail, and pop it back into captivity, would it not then be purged, and eaten ?

My mother had to pull my hand hard to get me away from the lumacaro. Back on the bouncing tram, I leaned drowsily against my mother and wondered about the snails I’d seen, whose fate teetered between sure death by salting and then the pan or perhaps freedom if they did manage to slip quietly away.

One year we cooked snails too. It was for my father’s birthday, June 20 or 21 (he could never remember which, and had long lost his birth certificate.) He loved snails, having developed a taste for them not in Roanoke VA, where he was born and grew up, but when after the Army he spent a blissful six months in Strasbourg. He studied French, drank good wines, recovered.. and discovered snails.

My mother, who had most of her adult life been vegetarian, was stoic. That year she visited the lumacaro in our neighborhood’s covered market, and brought home a kilo of snails. My father was lucky in the timing of his birthday, since to find the lumacaro in the Roman market in any other month would be impossible, and would mean harvesting your own in a friend’s garden. My mother had neither the heart nor the stomach to purge the snails, so she asked our sainted maid, Speranza, to do the job. And then that year, for my father’s birthday dinner, we had snails. Because my mother was not a French cook, but an Italian one, she could not replicate the snails in the Alsatian style, but she could make them alla romana.

I constructed a birthday crown for my father, he opened (with a loud pop) a very good champagne, and Speranza brought on the snails. Papa’ was absolutely delighted. My mother, always festive at parties, toasted my father, carried in the birthday cake, but did not touch the snails.

Much later, I went into the kitchen and found my mother seated at our marble kitchen table. I was amazed to see a plate of snails before her. In her hand was a large piece of the traditional Roman rosetta roll, and with it she was mopping up the fragrant tomato sugo.

“Mama !” I called out, amazed ! “So you do like snails after all ?”

My mother’s blue grey eyes smiled at me. “Lovey, I really don’t at all. But I just love the sugo.” And with that she piled more sugo upon her bread and popped it into her mouth.

Auguri di San Giovanni to all !